As the director of an industrial museum, I am fascinated by the digital revolution, which has opened up completely new worlds since the end of the 20th century. The emerging possibilities appear all the clearer when you examine similarities between the digital revolution and the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. This comparison gives reason to reflect on the disruption caused by such fundamental transformations. Starting from technical innovations, both revolutions describe not just partial but rather comprehensive changes that not only affect economies and the world of work, but also political and social processes and private life.

Industrial revolution

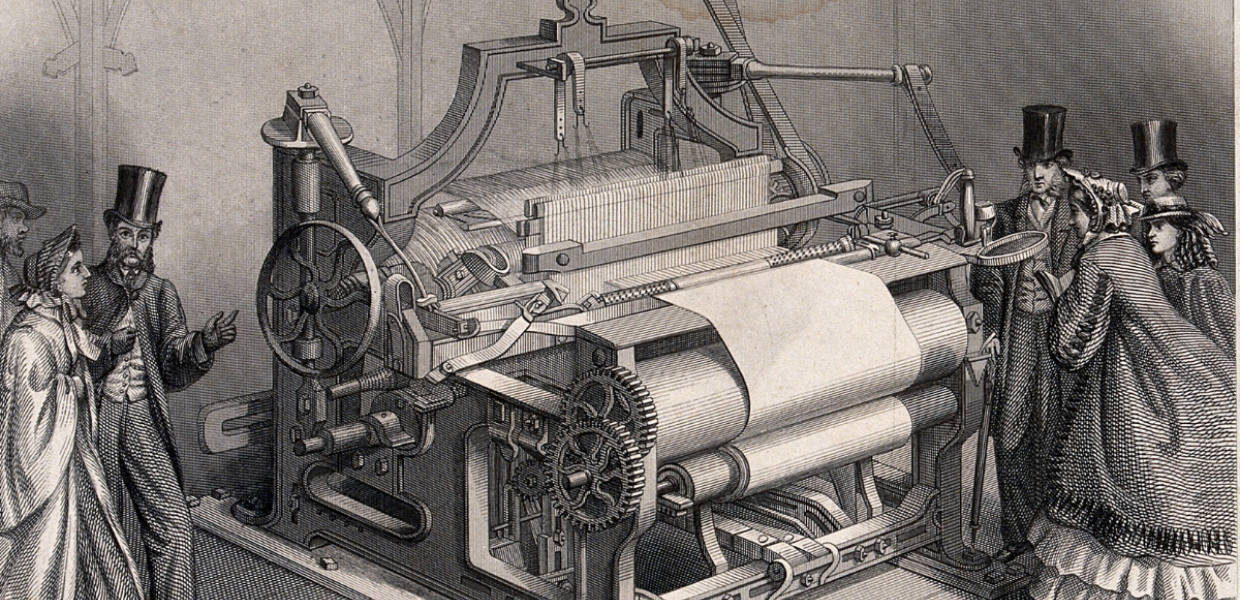

The State Textile and Industry Museum in Augsburg demonstrates many of the potentially positive dimensions of the industrial revolution through the display of objects such as running looms. Industrial capitalism not only provided many people with new jobs, but brought about mass-produced commodities that could be purchased by a broad population at reasonable prices. What used to be luxury became open to mass consumption. For example, cotton consumption per capita in Germany increased by a factor of 20 in the 19th century. Such a consumption revolution is illustrated by the pattern book collection in the State Textile and Industry Museum, which contains more than 1.3 million textile print samples.

It is no coincidence that the age of industrialisation coincided with the era of democratisation, which involved an increasing number of people in political processes. With the development of media like books and newspapers, the public sphere grew, which enabled more people to participate in political matters. Yet industrialisation also had negative dimensions, including the exploitation of working-class populations and the many manifestations of alienation - both in terms of the workforce itself and their relationship to manufactured products. The State Textile and Industry Museum has explored such negative aspects through exhibitions on the discrimination faced by women during this period.

Digital revolution

Digital possibilities have massively changed the consumption habits of the Western world. Our worldwide shopping mall is just a mouse click away. Global networking, propelled by the internet and social media, has already shown social and political impact. The internet also provides an abundance of - ideally open access - information to a world population that can thus acquire education, participate in culture and engage in political decision-making. When cultural treasures as well as political ideas are freely shared, the digital revolution serves democratisation, participation and empowerment.

Here, museums can become active. Soon we will put thousands of recently digitised photographs online, allowing digital access to the cultural treasures of the museum. Additionally, in 2019, the State Textile and Industry Museum had a temporary exhibition which dealt with the future of the socially diverse city of Augsburg. We invited around 100 people to work together to create visions for future living. Via Facebook and Instagram, we let a wider public participate in these ongoing processes.

The transformation of the public sphere, which began with the Age of Enlightenment, attains a new political quality in a digitally connected world. The fact that social media in particular is suitable as a playground for fake news and post-truth manipulation calls for reliable truth-clarification tools. Only with their help will the digital revolution be able to put itself at the service of political as well as social justice. Ultimately, all revolutions are both boon and bane - it is up to civil society – including myself – to make the best of it.