How to identify and clear copyright in collection items

This page shares information to help you to determine if, and which, rights exist in your collection items. This is an essential first step before one can assign an accurate rights statement.

This page shares information to help you to determine if, and which, rights exist in your collection items. This is an essential first step before one can assign an accurate rights statement.

The information on this page is complemented by our webpages on the available rights statements used by Europeana and how to select an accurate rights statement.

We also offer a training course on copyright when sharing data with Europeana through the Europeana Training Platform, part of the Europeana Academy. Register for the course.

Having an item in your collections does not necessarily mean owning its copyright. Copyright is not automatically transferred when a cultural object is endowed, gifted or otherwise added to the collection of a cultural heritage institution. Unless you made an agreement with the rightsholder of the work to transfer copyright, you do not own the copyright. This can be challenging when dealing with digital cultural heritage, as you will need to digitise, display and otherwise use the item.

The information below highlights some of the steps that you can take when identifying the copyright status of an item in your collections. It is mostly based on European Union legislation. This page should not be taken as legal advice. Please note that many of the copyright considerations will vary from one country to the other.

Once you have identified copyright in your collections, follow our training on ‘available rights statements’.

In order to clear copyright in your collection items, you should start by identifying whether the item is protected by copyright at all. Not everything that sits in the collections or fonds of an archive, library or museum is subject to copyright protection. It might have never been subject to copyright protection, or it might have been but protection has expired. In these two cases, the institution will not have to face any copyright barriers.

Copyright protects original works (works that reflect the author’s own intellectual creation), which among other things include literary works, dramatic works, art or films.

Some creations that do not meet the originality criteria, such as non-original photographs, non-original databases, or the recording of a phonogram, are also entitled to some rights in certain countries, with a shorter duration of protection. They consist of a copyright-type of protection and are called neighbouring and sui generis rights.

Among other things, copyright does not protect:

Works whose copyright term has expired

Content that does not meet the originality threshold

Ideas (copyright only protects their expression)

Natural artefacts (flowers, rocks, trees, songs of birds)

Mathematical problems and formulas

Governmental, legal and/or judicial documentation, under many legislations.

This is important as it means that not everything that sits in the collections of an archive, library or museum is subject to copyright protection. There is an 'originality' threshold that needs to be met. This is a rather difficult assessment to make, and the only person who can definitively confirm, from a copyright perspective, whether something is original or not, is a judge. Unfortunately, to be on the 'safe side', this results in a tendency by culture heritage institutions to consider most things sufficiently original, and therefore copyright-protected, even though they might not be.

The public domain consists of works that are not protected by copyright. They can enter the public domain after the term of copyright protection has expired, was expressly waived, or if the work was never protected by copyright.

The general rule in the European Union, as established by the Term Directive, is that a work enters the public domain 70 years after the death of the author, effectively starting on the 1st January of the following year. However, there are exceptions to this rule which make the calculation quite complex. The moment from which the counting starts varies depending for instance on the type of work, if the work was published, if it is anonymous or published under a pseudonym, or depending on the authorship. Terms of protection that are longer than the 70 years after the death of the author can exist in certain countries, as defined in national legislation.

There might also be works contained inside a work whose copyright protection expires at a later stage.

While determining whether a work is in the public domain can be very complex, there a few rules and criteria established in the Term Directive that are worth noting:

For anonymous or pseudonymous works, the term of protection expires 70 years after the work has been lawfully made available to the public.

For audiovisual works, the standard term of copyright is 70 years after the death of the last author among the principal director, the authors of the screenplay and dialogue, and the composer of music especially written for the film.

For works of joint authorship, the term of 70 years is calculated from the death of the last surviving co-author.

The rights of producers of phonograms expire 50 years after the fixation is made.

By reading the section above and taking the quiz, you have learned that not everything in the collections of a cultural heritage institution is subject to copyright protection, and that it is worth making that determination. However, many items are protected by copyright. In those cases, the cultural heritage institution needs to make efforts to ‘clear’ the rights or rely on a legal safeguard in order to make use of the materials in certain ways.

This section describes the main options that a cultural heritage can consider to do that, namely: relying on an exception to copyright for a specific use; obtaining permission; or following a risk-managed approach.

European copyright laws have a series of exceptions or limitations to copyright that allow individuals or institutions to use copyright-protected works without needing permission from the rights holder. In the European Union, most exceptions or limitations are designed to support a specific activity in a specific context, and there is no ‘general’ exception such as ‘fair use’ in the United States. Some exceptions and limitations widely recognised in the European Union cover:

The making of copies by cultural heritage institutions for preservation purposes

The publication online of out of commerce or orphan works (further described below)

To display of a work in a classroom

The citation of parts of a work for research purposes

These, and other exceptions and limitations to copyright, can be essential to support a cultural heritage institution’s activities. It is therefore important that cultural heritage professionals are informed of the possibilities that they offer in their countries. Exceptions and limitations to copyright are not fully harmonised in the European Union, but this resource by the Communia Association for the Public Domain, Open Future and Digital Republic can help you find more information.

If a cultural heritage institution does not own the copyright to the materials at stake, and there is no exception or limitation to copyright for the intended use, the institution will need to identify the rights owner and obtain the permission to use copyright-protected material.

In order to do that, it is worth noting that:

The rightsholder may have already transferred certain rights to the cultural heritage institution when the item was acquired.

It is possible that the author transferred the copyright to someone else, especially if the material was exploited commercially. This is the case, for instance, of the author of a book who transfers rights to a publisher, or the author of the song to a record company. This is the person/institution that can give permission to use the materials.

It is important to know in advance which permissions are needed. This intended use should be stated in the agreement with the rightsholder. For example, sharing a digital object with an aggregator, or allowing additional uses like education or commercial use.

Collecting societies (organisations that collect copyright royalties on behalf of authors) might be in a position where they can give licences to cultural heritage institutions to make collections available online, even if the author is not known or not in the collecting society’s repertoire.

If you cannot identify or locate the rightsholder to obtain permission, or the amount of items is too large to even consider undertaking such a process, consider relying on the out of commerce works provisions, which provide a solution based on a licence and an exception to copyright. You can find more information about this system on this page.

Alternatively, consider relying on the orphan works exception. This exception to copyright requires conducting a diligent search before you can rely on it to make the work available online. It is worth noting, however, that the experience of many cultural heritage institutions when relying on this exception has been rather unfruitful.

The last remaining option, that some cultural heritage institutions make use of, is taking a risk-managed approach, after carefully examining the risks and considering aspects such as whether the work was ever commercially available, its age, type or the intended use. You can read more about risk-management in this post and in this webinar by Naomi Korn, and in the second presentation of this webinar by Fred Saunderson.

When clearing rights to make an item in a cultural heritage institution’s collection available online, there are considerations that are closely linked to copyright that are worth taking into account. Below are a few.

From a legal perspective, there might be data protection or privacy concerns that challenge the sharing of the digital object online.

There can also be contractual limitations. For example, it is quite common that funding for digitisation comes with a number of conditions. A cultural heritage institution may have agreed that the publication or reuse of the digital reproduction is limited to certain circumstances. The person or institution that conducts the digitisation efforts, such as a photographer, may also have rights that need to be cleared, ideally via an agreement through which all rights are transferred to the cultural heritage institution. These various additional aspects need to be addressed in order to make the digital object available online

Last but not least, there might be ethical considerations. Copyright protection may have expired, but a cultural heritage institution should still consider whether sharing certain digital objects online and encouraging their reuse can lead to negative consequences for certain individuals or communities. You can read more about the balance between opening up and ethics in this set of recommendations by Creative Commons and in the Europeana Public Domain Usage Guidelines.

Cultural heritage institutions should also consider being explicit about the fact that no rights arise, or no rights are recognised, on the digitised copy of an item. If the item is protected by copyright, restrictions would exist anyways. Removing rights on the digital copy is therefore particularly important when the item is in the public domain: in those cases, the cultural heritage institution is depriving users of an opportunity to use the material without copyright limitations or conditions.

Europeana, through its Public Domain Charter, encourages cultural heritage institutions to never claim rights on digital reproductions of public domain materials, and considers that it goes against the public interest mission of a cultural heritage organisation to do so.

The very few situations in which such rights might arise are described below for clarity, and not to support making use of them.

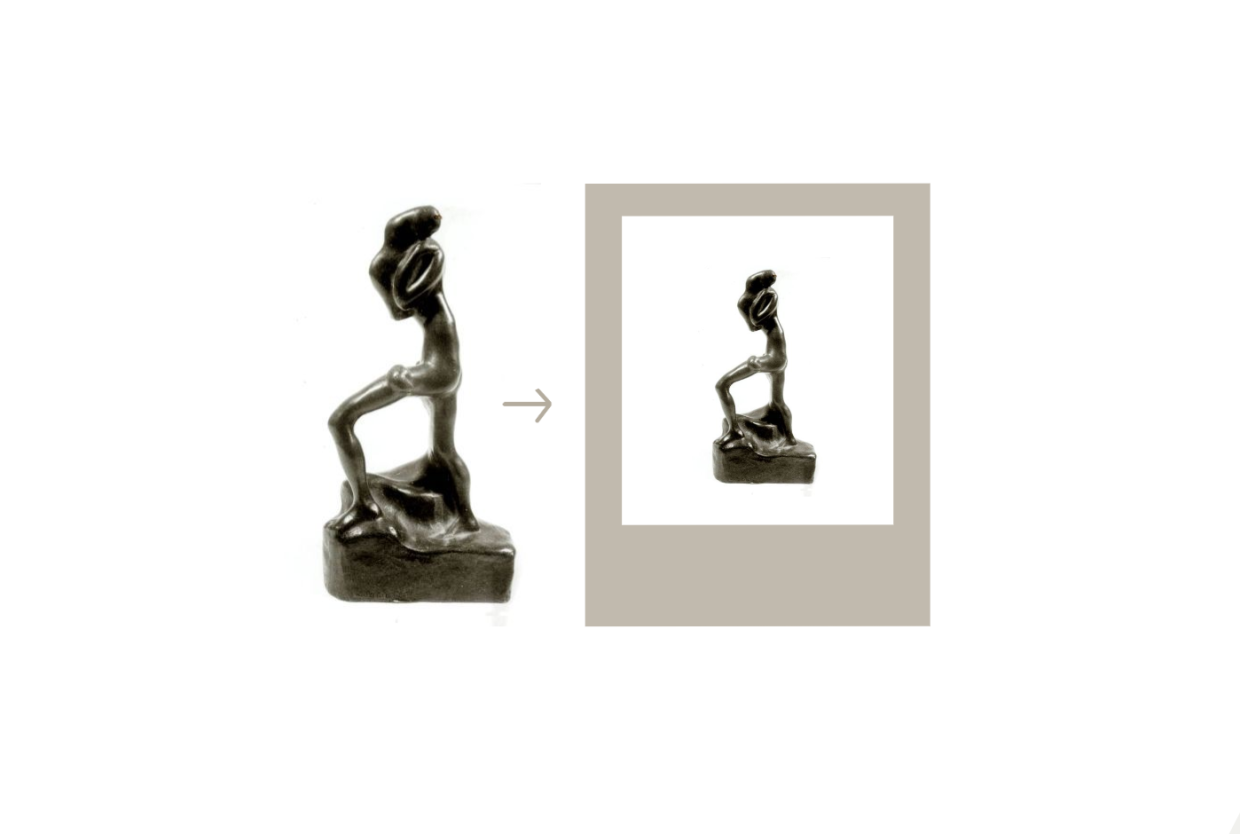

Digitisation processes (e.g. scanning, taking photographs of 2D and 3D objects) can only trigger copyright protection if the digitised replica meets the European Union standard of originality, which requires that the work is the “author’s own intellectual creation.” If the reproduction (the digital copy) can be considered a new original work in its own right, the person behind the digitisation of the object obtains full copyright protection. In most cases, digital objects created through digitisation will not meet the required originality threshold and will not qualify for any form of protection based on copyright.

Copyright-related rights to non-original photography are recognised in some member states, and these could potentially apply to digital reproductions of physical items. However, the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive has established that it is no longer possible to claim such rights on digital reproductions of works of visual arts that entered the public domain.

As a result, there are very few cases in which it is possible to claim, with a legal basis, copyright or copyright-related rights on the digitisation of a work.

Once you have finished reading this page, we invite you to continue learning about this topic by going to the page ‘Available Rights Statements’.

You can read more about copyright management in the Copyright Management Guidelines for cultural heritage institutions by the Europeana Copyright Community.