In a quiet gallery in a Western museum, a sacred object from Zambia rests behind glass. It might be a clay mbusa figurine from a Bemba Chisungu initiation, once used by elder women to mould a girl into womanhood through secret teachings on social responsibility, becoming a woman and the physiology and psychology of being a woman. Or perhaps it is a Makishi mask, which for the Luvale and related peoples is not a costume but the living embodiment of an ancestor, whose power is activated within the secluded, sacred space of the mukanda male initiation camp. To the uninitiated, its purpose was to be unseen, its knowledge guarded. Today, it is exposed to the casual gaze of thousands, its story flattened by a small text panel.

This act of display, seemingly one of preservation and education, is in fact a profound dislocation. The journey of such objects from the firelight of a ritual enclosure to the sterile illumination of a museum vitrine is a story of colonial extraction and epistemic violence. The glass box is not a neutral frame; it is a colonial one that strips the object of its context, silences its power, and violates the very secrecy that gave it meaning.

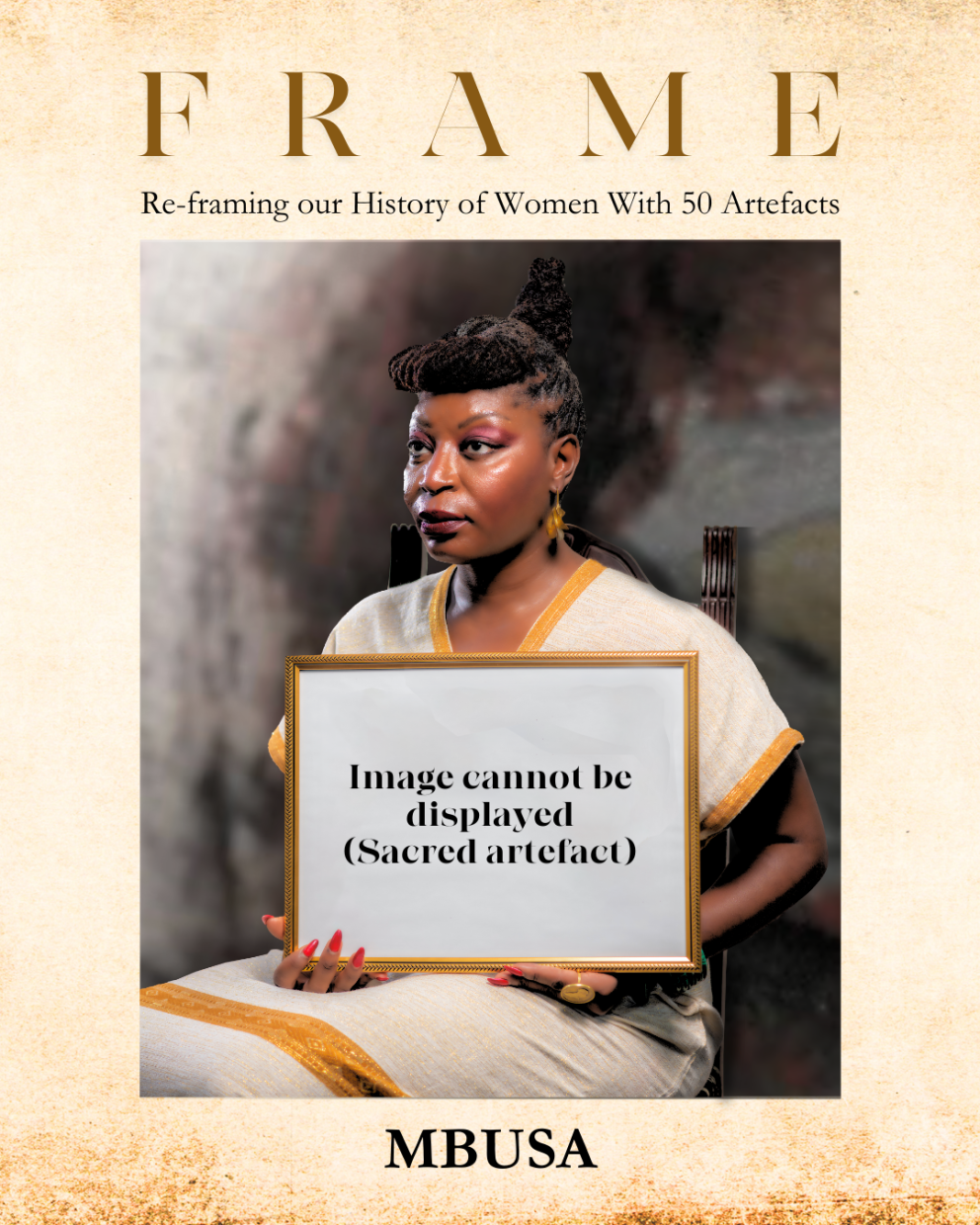

Now, a growing decolonial movement is forcing a radical reckoning within these institutions. In a move that seems counterintuitive, museums across the world are beginning to cover their displays and empty their vitrines. They are doing so not to hide these objects, but to finally begin to see them for what they are, by acknowledging that for some sacred items, the most respectful and honest form of display is no display at all.

From living archive to silent artifact

In Zambian societies, as in many indigenous cultures, knowledge is not a static text to be read but an embodied experience transmitted through performance, ritual, and tangible teaching aids. The secrecy surrounding initiation rites was not about arbitrary exclusion; it was a crucial mechanism for preserving the integrity and potency of this knowledge. The learning process was personalised and experiential, designed to transform the initiate physically and socially. To make this knowledge openly accessible would be to risk its misinterpretation and desecration, diluting its power and rendering it ineffective. The mbusa emblems, for example, are meaningless without the accompanying songs, dances, and esoteric instruction from the banacimbusa (female elders). The awe and fear inspired by a Makishi ancestor depends on the strict separation between the initiated and the uninitiated. These objects were never meant for public consumption; their agency was contingent on their restricted context.

The colonial encounter violently disrupted this system. Missionaries and ethnographers, operating within the colonial project, collected these objects under a ’salvage’ paradigm, claiming to preserve cultures they were simultaneously working to eradicate or transform. This process, which scholars call ’musealisation’, is a form of death. The object is severed from its lifeblood—the community, the ritual, the secret knowledge—and is reborn as something else entirely: an ethnographic specimen, a scientific curiosity, or a work of ‘primitive’ art.

Once inside the museum, the object is subjected to a Western framework of knowledge that privileges the visual. Placed in a well-lit vitrine, it is offered up to the ‘empire of sight’, to be analysed for its form, material and aesthetic qualities. Its spiritual power and pedagogical function become secondary, often reduced to a brief, essentialising description on a label. The museum, through its very architecture and display techniques, asserts its authority to define the object, transforming it from an active agent in a living culture into a passive ‘dumb’ thing whose story is told for it.