The Swedish National Museums of World Culture comprise four separate museums with different thematic orientations, housing collections from all over the world and covering thousands of years of human culture from prehistoric times to today.

For several years, the Museums have been working on Ongoing Africa, a project focusing on objects, images and archival material from Africa and the Caribbean in the collections of the National Museums of World Culture. This includes objects from African and Black history collections which were collected during the colonial era and have over the years been used to tell and retell a colonial history and understanding of the world. ‘With Ongoing Africa, we worked with representatives of the African diaspora in Sweden and tried different ways to look at these collections anew,’ says Johanna.

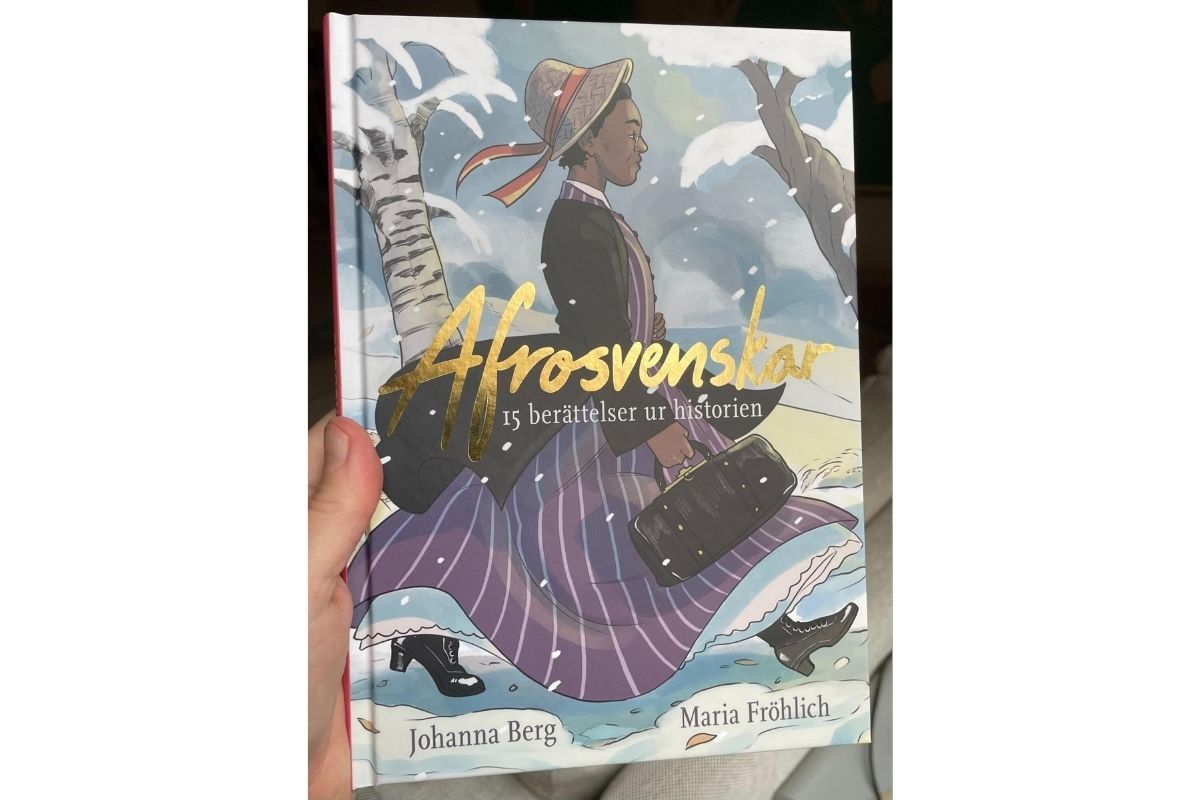

One of the latest outcomes of Ongoing Africa is a digital interpretation of 15 stories about Black lives in Sweden - The History of Afro-Swedes. The project seeks to illuminate the connections that have long existed between Sweden and Africa by highlighting examples of people of African origin who came to live in Sweden.

‘Africans in Sweden were never numerous,’ says Johanna. ‘And so their history is neglected or forgotten. There’s a narrative that says Sweden was homogenous in the olden days, but Afro-Swedes form part of Swedish history.’

Curiosity-driven research

The Swedish National Museums of World Culture collect objects from all parts of the world except Sweden and so Johanna had to examine collections from other archives and museums to find information about Black people in Sweden that could complement the Museums’ own collections.

The research process wasn’t easy. Johanna says, ‘Finding references to African people in the archives is hard. In newspaper cuttings, you might be able to find references to Black people under wordings that we’d rather not use today, while in parish records, for example, ethnicity is not often signalled in any way. There is no way to tell if someone by the name of Jack Johnson, for example, is Black.’

For other institutions looking to surface Black history from their collections, Johanna advocates looking with curiosity. ‘Most museums have a dominant narrative - they look for what is typical or representative or common, but as Black people in Sweden were few and far between, they never fall into that realm. That makes them hard to find. So one thing you can do is to allow yourself to really look into people within your dominant narrative but in a way that looks for difference. A lot of the Black people in Sweden in the 18th and 19th centuries lived similar lives to other people in Sweden at the time. But they were also different and unique.’

Gathering together small fragments of information from different sources, Johanna had the difficult but fulfilling task of putting the pieces together. ‘It takes curiosity,’ says Johanna. ‘You have to pull fragments together from different places to make sense of the history. In our research, we had to use outdated terms as a finding tool, which isn’t pleasant, but this doesn’t have to mean that you use those terms in your communication afterwards, and we haven’t - I’m happy with the decisions that we made in this aspect. And we’ve had positive reactions from our audience.’

The result is a series of 15 stories about both famous and unknown Swedes of African origin, with new visual interpretations and portraits by Maria Fröhlich, an illustrator and children’s author.