Mapping Migration in the arts: The Real Face of White Australia

As part of the Europeana Migration campaign, we highlight initiatives relating to migration and culture beyond our own network.

- Title:

- Real Face of White Australia

- Creator:

- Tim Sherratt

Throughout 2018, Europeana Migration will focus on how migration to, from and within Europe has shaped our cultural heritage. In the run-up to the campaign launch, we are featuring a number of interviews with arts and cultural heritage professionals working on projects related to migration, to shine a light on other initiatives showing the cultural sector’s response to this topic.

This time, we speak to Tim Sherratt, Associate Professor of Digital Heritage at the University of Canberra, who has led a project called The Real Face of White Australia.

Tell us about The Real Face of White Australia

The Real Face of White Australia is a series of projects aimed at increasing awareness and use of a powerful set of historical documents created in the administration of the White Australia Policy in the first half of the twentieth century. These records are now preserved in the National Archives of Australia.

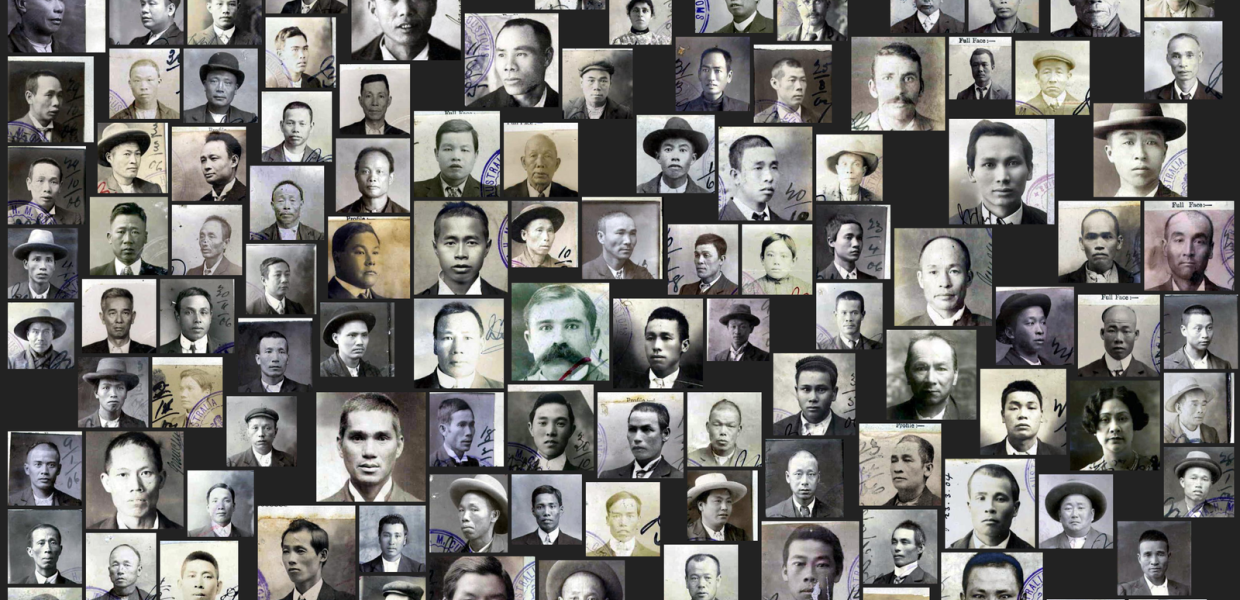

The documents themselves are visually striking – particularly the identification certificates which often include portrait photographs and handprints. Back in 2012, Kate Bagnall and I downloaded thousands of digitised copies from the Archives’ database and ran them through a facial detection script. The result was a seemingly endless scrolling wall of faces – a totally different way of seeing the records. Instead of files or metadata, you could see the people inside.

As well as the photographs and handprints, the documents also contain lots of information about ordinary people whose lives were monitored and controlled under Australia’s racist immigration policies. In 2017, we worked with undergraduate students at the University of Canberra to create a website where the documents can be transcribed – creating a valuable dataset for continuing research.

What was the White Australia Policy?

In the early twentieth century, Australia defined itself as a ‘white man’s country’, yet the reality was something different. As well as Indigenous Australians, there were many thousands of non-Europeans living and working in Australia, including Chinese, Japanese, Indians, Afghans, Syrians and Malays. Many of them were born in Australia, too.

Starting with the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, the Australian government introduced a program of legislation that discriminated against non-Europeans. This became known as the White Australia Policy. These laws concerned things like immigration, citizenship, the right to vote, social security and employment.

Under the Immigration Restriction Act, anyone entering Australia who was deemed not to be ‘white’ could be subjected to a ‘Dictation Test’. Despite its name, no-one was expected to pass this test – it was the mechanism for excluding those who didn’t fit the image of White Australia. Officials could choose the language of the test – it wasn’t just given in English – to make sure the arriving passenger failed.

The Immigration Restriction Act meant that thousands of non-European people already living in Australia now had to carry special identification documents when they travelled overseas. Otherwise they could be subjected to the Dictation Test and denied re-entry. Many thousands of these documents – called Certificates of Domicile and Certificates Exempting from the Dictation Test – are held by the National Archives.

Who has been involved in the project?

Kate Bagnall is a historian of Chinese Australia who has been working with these records for many years. My research is focused on politics and possibilities of digital cultural collections. We’ve both long been interested in how we can use digital technologies to open the records, and tell some of these stories online.

We’ve also involved students from the University of Canberra. Students in my Exploring Digital Heritage class are expected to work on a digital project, so in 2017 we worked together to develop and promote a site for crowdsourced transcription of the White Australia records. The site uses the Scribe Framework, a community transcription platform developed by Zooniverse and the New York Public Library. This part of the project was also supported by the University’s Centre for Creative and Cultural Research.

Of course the project was only possible because the National Archives of Australia had already digitised a large number of the documents and made them publicly available online. We were also supported by the Museum of Australian Democracy, who helped us launch and publicise the project in 2017.

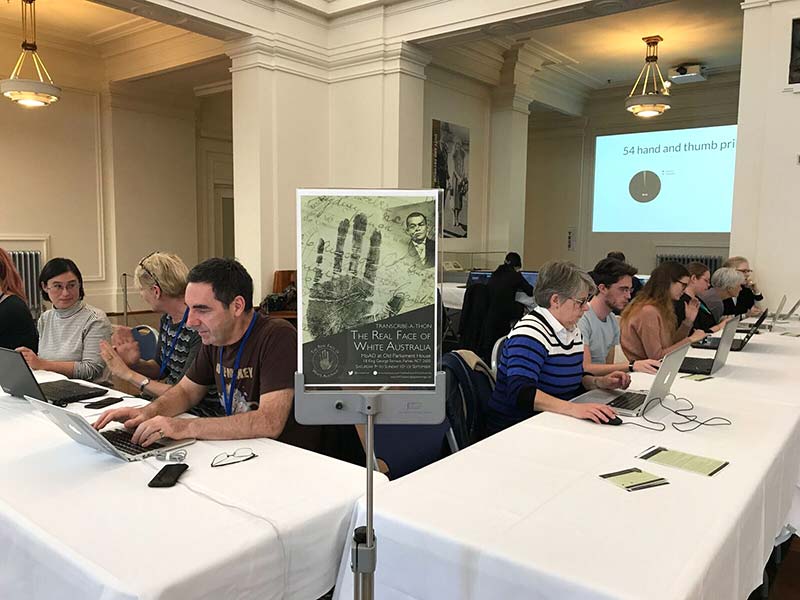

Volunteers during the transcribe-athon at the Museum of Australian Democracy, photo courtesy of Tim Sherratt

What has happened?

We launched the transcription site in September 2017 at a weekend-long ‘transcribe-a-thon’ held at the Museum of Australian Democracy in Australia’s Old Parliament House in Canberra. The Scribe framework breaks the transcription process down into a series of self-contained steps – marking, transcribing and verifying. Over 2,000 documents were marked and classified during the transcribe-a-thon, with many people joining in via social media.

As the documents are transcribed and verified through the website, data and images are made publicly available through a GitHub repository. So far we have verified data for more than 800 certificates. There’s still plenty of work to do – join in at http://transcribe.realfaceofwhiteaustralia.net/.

I’ve created a Twitter bot that shares micro-stories and photos from the transcribed documents. You can follow it at @invisibleaus. We’re also working with a group of researchers in Melbourne to add another set of records relating to the White Australia Policy – this time registers rather than certificates – to the site.

It’s always been important to us to remember and respect the people whose lives are documented in these records. By transcribing the certificates – extracting information about their names, their ages, their places of birth, their travels overseas – we hope to learn more about them and their experiences; to reveal more of the ‘real face’ of White Australia.

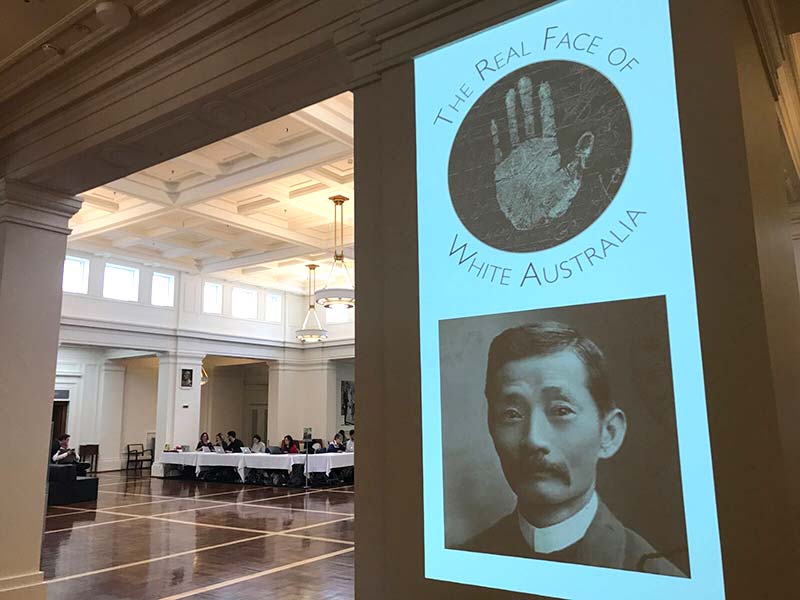

But the project is not just about transcription, it’s also about awareness – about exposing these records and acknowledging this history. There was some symbolism in the fact that we launched the project in Old Parliament House, where many aspects of the White Australia Policy were planned and implemented.

As well as hosting the ‘transcribe-a-thon’, the Museum of Australian Democracy allowed us to use their digital projectors in the main hall at the centre of Old Parliament House. Perhaps the most powerful and moving moment for me was to see the faces of some of the people who lived their lives under the weight of the White Australia Policy projected in that space.

Projections on the columns of King's Hall, Old Parliament House, photo courtesy of Tim Sherratt